Originally posted Mar 03, 2025 on Substack (hate it!)

Something that was important about X was the ability to share (and simultaneously bookmark) things I’d read or come across. I that are.na is meant to be about this, a way to build a ‘digital garden’ of the things you want to keep, so I’d be interested in people’s experiences with are.na and if they’d recommend it. (Can are.na also be a blog / can you also make posts on there?)

(Just in general what are the online social ecosystems and infrastructures that we can create outside of the like 3 websites that exist, including Substack? As a teenager I had a Blogspot, which is owned by Google, and then for this current thing I wanted to use Tinyletter but it doesn’t exist anymore, so I settled on Substack even though I have ethical qualms about it as a platform… Short of just emailing each other, what are other things we can be doing?)

Anyway, here are some things:

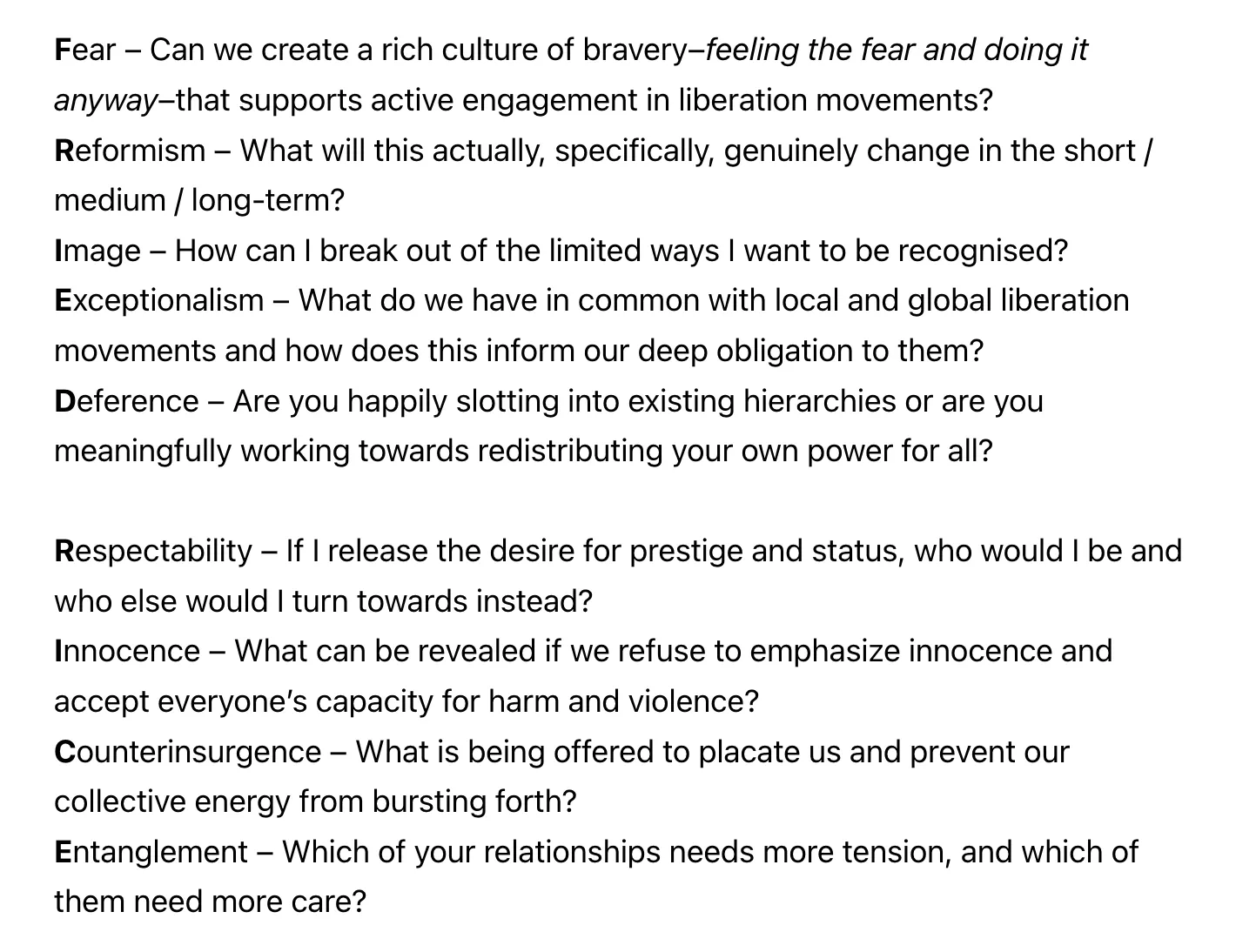

Pear Nuallak’s incisive and essential piece on the ‘fried rice’ of representasianism, which kindly ends with 9 important questions to always keep in mind and refer to:

Image: Screenshot from Pear’s essay.

Image: Screenshot from Pear’s essay.

I had a really great chat with Pear the other day and a film they watched recently and have been thinking about a lot is Tongpan (1976), a Thai meta-documentary, which can be found for free on YouTube here. I then watched it myself and I was struck, again, by this thing I’ve been thinking about, the affordances of the moving image / the cinematic form in that it allows you to portray someone doing a repetitive action (Tongpan and his wife taking turns shovelling water out of the canal, Hong Chau creating her sculpture in Showing Up, the construction workers in Still Life demolishing buildings by hand and the repetitive swing movements of their sledgehammers…), to have the camera just linger on them doing that. I’ve been thinking about how much harder it is to ‘watch’ in the same way in prose, because prose is inevitably linear, meaning that you inevitably have to create some kind of hierarchy, and because the moving image takes control of time and the viewer’s time in a way that would be harder to capture via the linearity of text.

Image: From Jia Zhangke’s Still Life, 2006.

Image: From Jia Zhangke’s Still Life, 2006.

Image: Courbet’s The Stone Breakers, 1849.

Image: Courbet’s The Stone Breakers, 1849.

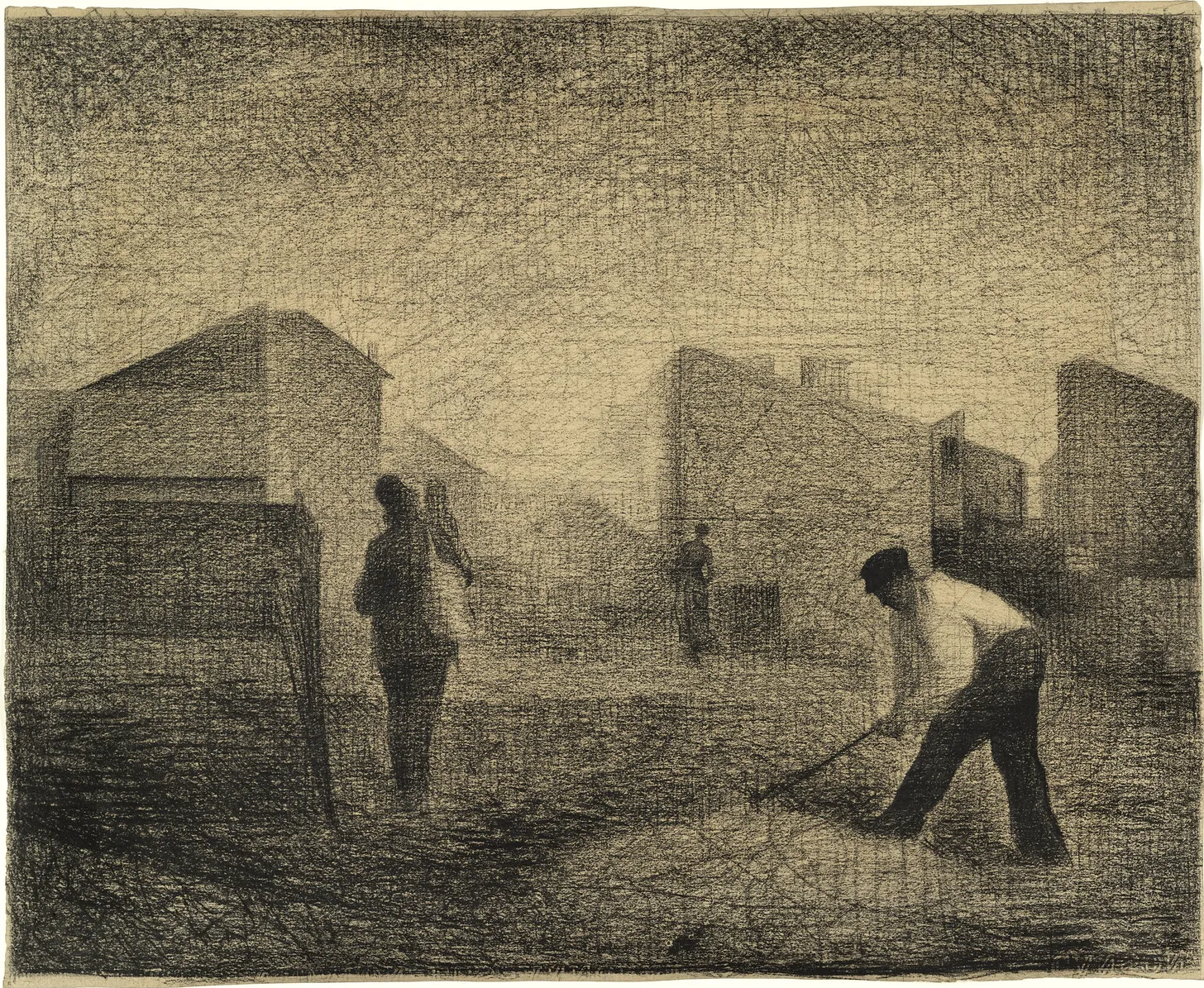

Image: Seurat’s Stone Breaker, Le Raincy, c. 1879-81.

Image: Seurat’s Stone Breaker, Le Raincy, c. 1879-81.

(What does it mean that these three images above, which have all lived rent free in my head for years together, are all by and of men?)

I don’t know if I’m making any sense, but essentially, you could hold a camera and film someone building a wall, brick by brick, for 30 minutes, but how do you achieve that effect if you’re writing prose?

One answer is that prose can’t do it, which is where poetry and other unconventional text forms come in, as well as obviously just other media in general. But I want to stay with the trouble of prose. I like prose and I’m interested in working with it.

Another answer is that most people don’t want to watch the 30 minute film either, would probably want to skip it or fast forward. (When Zhang Peili presented 30x30 to his peers at the Huangshan conference in 1988, one audience member famously asked him to fast-forward to the point when something was going to happen, and, obviously, in this mythology surrounding the birth of video art in China, there is no such point!)

A third answer is that prose gives us an insight into the internality of the brick-layer, in a way that the still camera that ‘watches’ the brick-layer can’t. Prose can tell us exactly what the brick-layer is thinking about, feeling, or remembering. But what if I want that to be opaque? What if I want to linger on the repetitiveness and embodiment of the brick-laying?

Speaking of opacity, I’m never not thinking about this line in Glissant’s ‘For opacity’, translated by Betsy Wing:

As for my identity, I’ll take care of that myself.

The possibilities of this sentence! The use of the word ‘take care’! What’s also interesting is that, in looking for this quote again just now, I was reminded of the passage in which it’s used, which is something I had less memory of. The whole passage goes like this:

And now what they tell me is, “You calmly pack your poetics into these craters of opacity and claim to rise so serenely beyond the prodigiously elucidating work that the West has accomplished, but there you go talking nonstop about this West.” —“And what would you rather I talk about at the beginning, if not this transparency whose aim was to reduce us? Because, if I don’t begin there, you will see me consumed with the sullen jabber of childish refusal, convulsive and powerless. This is where I start. As for my identity, I’ll take care of that myself.”

As we know, I don’t think that ‘childish refusal’ is ‘powerless’, so I think it’s interesting that he makes that statement. I’m not a big Glissant expert so if anyone has thoughts about what he means here and where he’s coming from, I’d be really interested!

One of the reasons why this whole question (of the work of art that ‘watches’ someone working) has become really important to me is because, a little over a year ago, I watched Zhao Liang’s 2015 film Behemoth, which is, on the one hand, a documentary about coal and steel workers in Inner Mongolia, and on the other, an abstract monologue inspired by the Divine Comedy. A lot of the footage of the factory workers is presented with zero explanation or commentary, so I spent most of the film trying to figure out what it was they were doing in the footage, and realising that I didn’t know a single thing about heavy industry even though it powers all of our lives. Ever since watching that film I’ve been thinking / wondering a lot more directly about heavy industry, logistics, scale, materiality, personal relationships to and in capital, depictions of labour, and the opacity of the figure in the shot, and that relationship between the figure depicted in the shot/image/text and the audience who ‘watches’ them (and of course with the author inbetween and how that mediation is happening).

I’ve been slowly trying to watch more stuff by Wang Bing, and have seen like 3 hours of 铁西区, but it’s hard to focus on this kind of stuff when it’s not part of the immersive experience of the big screen, which goes back to the thing about how most people don’t even want to watch this stuff in the first place, so it’s not like there’s a binary in which the cinematic portrayal of a brick-layer is somehow automatically more successful than the prose text portrayal.

I’m currently reading Pig Earth by John Berger which I think does a good job of depicting the labour in this fairly straightforward, subjective yet opaque manner. I also really enjoyed taking a workshop called ‘Writing the workplace’ with Kyle Lucia Wu a few months ago, which was held through Workshops4Gaza, which also has a lot of really cool workshops that you should check out.

Anyway what do you think? Sound off in the comments below.

Meanwhile, more links:

Thảo Tô’s award-winning short story, ‘Love in the time of migration’ in Wasafiri.

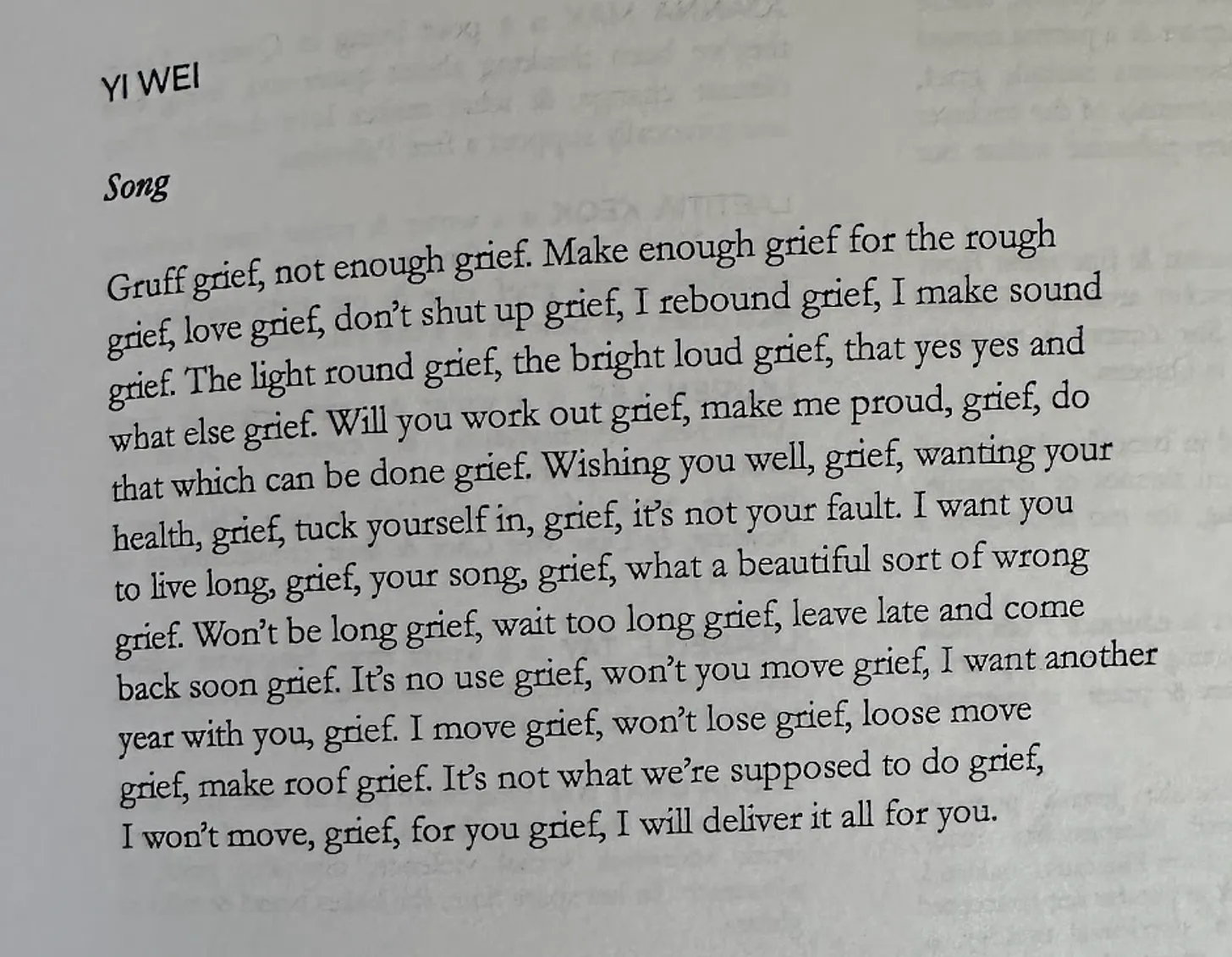

This rhythmic, entrancing, hard-hitting poem by Yi Wei (originally published in Sundog Lit), featured in a chapbook to fundraise for families in Gaza edited by Laetitia Keok, A Poem is a Garden, which you can receive if you donate $15+ USD to any campaign on gazafunds.com:

This interview with 3 editors of Pinko Magazine in Full Stop about Pinko’s project as a whole and their book After accountability. Some extracts:

M E O’Brien: […] it’s kind of the question of gay communism. Like in what kind of society could an erotic social bond be a source of solidarity and transformation between people?

and:

M. E. O’Brien: […] when [accountability processes] don’t work, it’s often a kind of crisis of community and falling apart of community. And so, we developed this Marxist argument, drawing on the Marxist idea of separation, that we actually are immensely interdependent with huge numbers of people around the world. But that interdependence is mediated by the impersonal exchange of the market. We are connected, one might say accountable to huge numbers of people who we’ve never met, who we don’t have any social relationship with. And who, instead, whose work is somehow involved in the reproduction of our lives and our work is somehow in the reproduction of their lives. This is the community of global capital that constitutes our lives, that’s mediated by the market. And within that, there are a few relationships of direct personal domination within the market that are highly accountable. And those are your employer and your landlord, right? Those are like really accountable relationships, where you better stay accountable or it’s going to be really consequential.

[…] within this, we have all these aspirations and desires to think of us as living in a community of people that we share political commitments with, we share erotic life with, we share social networks with, people that we might care about a lot and might reflect something of the world that we want to live in.

[…] when we speak of community, we’re speaking of the world that we want to live in. And that world would actually require either the means of production, the means of reproduction, the means of survival, being directly, democratically owned by a community, or being universally available to people, and social relations not structuring people’s access to these things. And those are two different versions of what we could call communism, right? Of what we could call the overcoming of class society and racial capitalism. And so, the sort of problem of accountability goes very deeply into how we have these romanticized, mythologized, inverted understandings of our social world as it exists under capitalism.

and:

Max Fox: In some ways, the accountability story is one of a kind, a reparative or rear-guard action to kind of put the elements of that evanescent and embattled but crucial community back together after these attempts at making any sort of advance. Michelle [M.E.] talks about how, as any sort of social movement is in excess, it’s in excess of its organizational capacity. It’s in excess of what it’s capable of doing. But it does it. And that’s the only way that it’ll ever succeed. But it’s only retrospectively that we’ll realize that what was present was sufficient. And so . . . to return to this, maybe it sounds more negative than it is, this theme of failure and accountability. It’s this organizing principle in our study because that’s what you have to work with, basically, until we win.

I haven’t actually read After accountability but it definitely seems like it raises a lot of pertinent questions. I also have been wondering about oral history as both methodology and form, the ways in which oral history can be used fictionally (ME O’Brien co-authored Everything for everyone, which I really need to read) and the possibilities of collective voice and collective perspective in fiction and narratives.

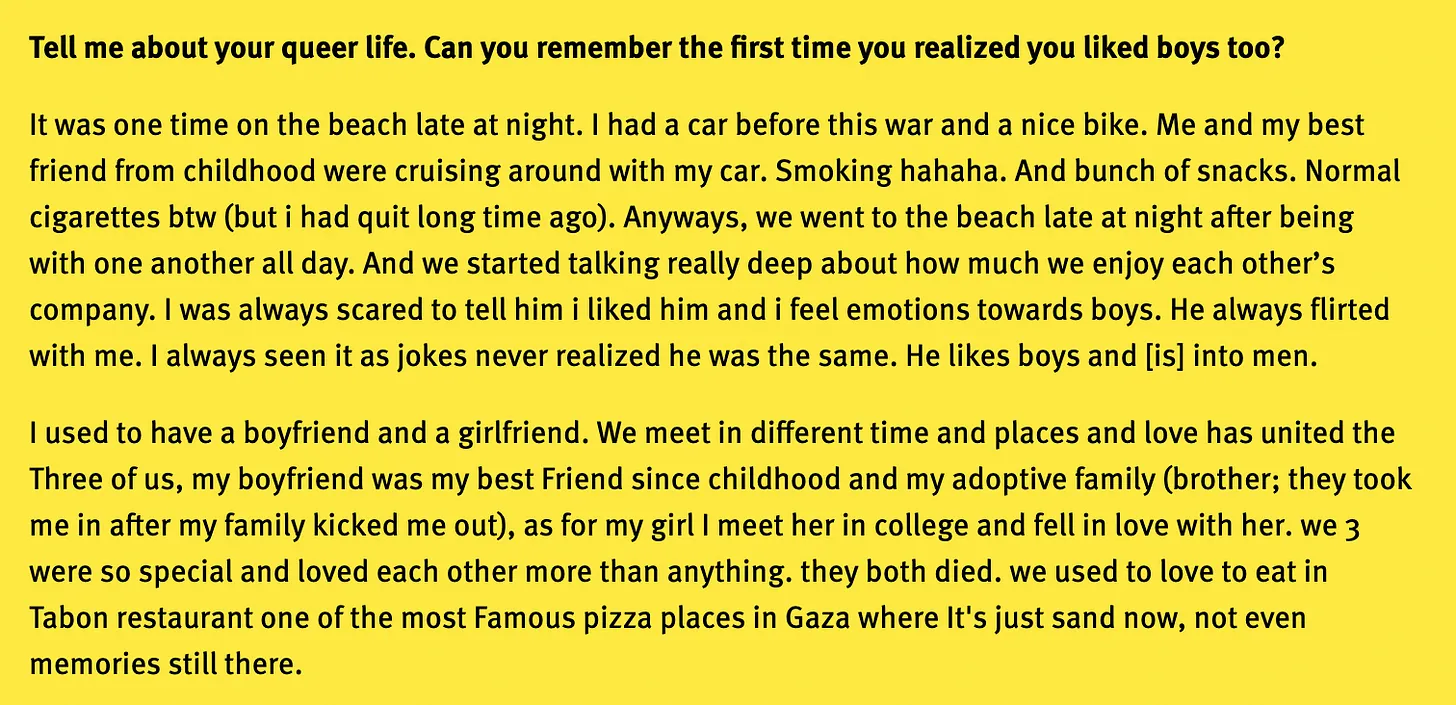

By the way, I also love this piece by Afeef Nessouli in Pinko’s Queer Palestine, and this passage specifically from the interview with QFG:

As well as this article by Pinko editor Max Fox, about Kiyoshi Kuromiya, a very multifaceted figure.

A couple of months ago, when I first read this article and sent it to a couple of my friends with a screenshot of this exact paragraph, my friend E. was like, “Oh, I thought this was one of your works of fiction,” which was funny, because it really doesn’t read like an extract from a short story, but maybe it’s a sign that I need to start contextualising the things I send to people more.

Another final thing is that, yesterday, I was reading a bit about the Grunwick strike of 1976-8 and found out that the Grunwick factory was actually a photo film processing factory, making the Grunwick strike a history of art. Excitingly, it looks like Dr Rowan Lear has done some work on this, as well as Dr. Kirsty Sinclair Dootson, though I can’t find anything published (yet).

Image: Screenshot from a 2021 conference programme lol.

Image: Screenshot from a 2021 conference programme lol.

Image: Screenshot from here.

Image: Screenshot from here.

Anyway I’m reaching my length limit it seems, but this is fun because I’m also thinking through my relationship to art history and to study, figuring out what it is that I love and can do, and what it is that I hate and can’t stomach doing anymore.

Let me know what you think!!

Jiaqi